![]() The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia

The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia

|

| Previous: Trona | Table of Contents | Next: Trucks |

NOAO

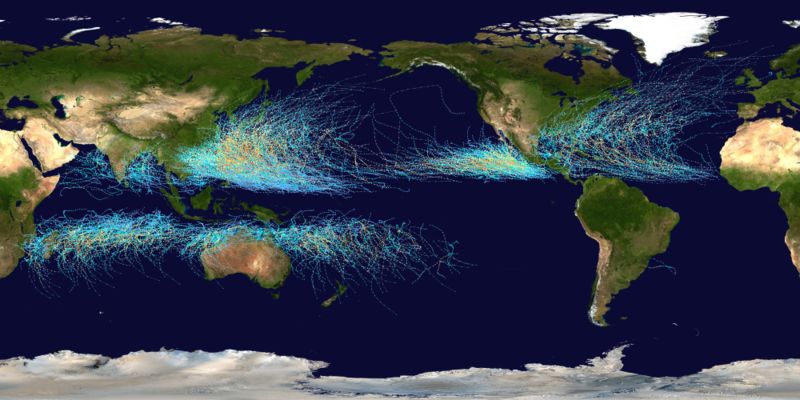

Tropical cyclones, known as typhoons in the Far East and as hurricanes in the Western Hemisphere, are probably the most destructive storms on earth. They begin as disturbances near the Intertropical Convergence that move away from the equator and begin spinning under the influence of the Earth's rotation. If the disturbance is over very warm waters, and if other conditions are just right (and not all the necessary conditions are understood, even today) then the disturbance creates the right conditions for the rapid rising and cooling of the warm air over the ocean, driven by the heat released by the condensation of the ample moisture in the air. More warm, moist air flows into the storm, which becomes a powerful heat engine, up to three hundred miles across, which converts the energy of the warm ocean waters into violent winds and torrential rain. A central eye forms, in which there is no precipitation and only light winds, which is surrounded by a wall cloud in which winds can exceed 160 miles per hour (260 km/h). The force of the winds pulls the ocean surface into the storm, producing a storm surge that combines with the rain and wind to produce flooding.

There are six breeding grounds for

tropical cyclones around the

world. Five are directly relevant to the Pacific War. The first

is the eastern Pacific off

the coast of Mexico. The

typhoons formed here tend to drift

west and die out

over open water, but they pose some hazard to shipping coming

through

the Panama Canal,

and occasionally one will drift north and east and threaten

Mexico. The second

breeding ground is in the waters along northern Australia through

the Solomons

to Polynesia. The

storms

formed here drift east and south, sometimes threatening the South

Seas

islands

or the north coast of Australia. The third breeding ground, and

the

largest in

the world, is the west Pacific around the Philippines.

Many typhoons are spawned here every year, and they proved to be a

great

hazard

during the Pacific War. The fourth breeding ground is the

south Indian Ocean,

and the storms that form here tend to drift south and die out over

open

water far from shipping lanes.

The fifth and smallest breeding ground is the Bay of Bengal; though few

storms

form here, those that do are among the most deadly, because they

tend

to

drift north and bring catastrophic flooding to the shallow delta

of the

Ganges and Brahmaputra

Rivers.

The sixth

breeding ground is in the Atlantic west of Africa. Although not in

the Pacific theater, this breeding ground indirectly affected the

Pacific War: A severe hurricane season in 1943 dropped production

of gasoline from Gulf Coast

refineries by half a million barrels daily for several weeks.

Because of the great importance of weather to the conduct of the war, both sides took pains to gather as much weather information as possible. It was during the Pacific War that a U.S. Navy Avenger became the first aircraft to deliberately fly into a tropical storm with a meteorologist on board. Submarines regularly reported weather information from ocean areas inaccessible to conventional reconnaissance. But cyclone detection and track prediction remained primitive, and tropical cyclones could spring a most unpleasant surprise on a military commander. 3 Fleet under Halsey twice blundered into the path of typhoons (on 18 December 1944 and 5 June 1945), and Yamamoto's successor, Koga, was lost when his plane went down in a typhoon off the Philippines.

The typhoon of 18 December 1944 illustrates the

threat posed by these storms. The typhoon struck as 3 Fleet (seven

fleet carriers; six light carriers; eight battleships; 15 cruisers; and 50 destroyers) and its

replenishment group (12 fleet

oilers, three fleet tugs,

five destroyers, ten destroyer

escorts, and five escort

carriers) rendezvoused for refueling on the morning of 17

December in the eastern Philippine

Sea.

A 25 knot (45 km/h) trade wind slowed refueling, but there was no

particular indication of any oncoming storm. The rapid advance of

the Allies

meant that the area was not yet well covered by weather stations,

and

reconnaissance aircraft tended to avoid poor weather and to delay

reporting weather conditions until they landed. This left the

fleet

vulnerable to a small, rapidly intensifying storm, which is

exactly what happened.

The 3 Fleet meteorologist estimated on the afternoon

of

17 December that there was a weather disturbance 450 miles (720

km)

east of the Fleet, too far out to be of immediate concern, and the

worsening sea conditions were attributed to the brisk trade wind.

Halsey ordered his fleet to steer northwest to an alternate

refueling

rendezvous that he though would take the fleet away from the

disturbance. In fact, the "disturbance" was a small but powerful

tropical cyclone that had rapidly intensified and was now just 120

miles (200 km) southeast of 3 Fleet. As the weather

continued to

worsen, Halsey changed course two more times, but the final course

took

part of 3 Fleet directly into the storm's path.

By 0400 on 18 December weather conditions were becoming alarming,

but

the barometer held steady, leading Halsey and his weather officer

to

believe that conditions were not that bad. At 1000 the barometer

began

rapidly falling, and the seas had become "mountainous" by 1130.

The eye

of the storm could now be seen on SG radar. At

1345 Halsey finally issued a typhoon warning.

The battleships and fleet carriers rode the storm out reasonably well, the latter losing no aircraft. The light carriers fared much worse, and many of their aircraft tore loose from their lashings and were washed overboard or crashed into each other and burst into flames. Monterey and Cowpens caught fire from burning aircraft, though the fires were quickly brought under control. A total of 146 aircraft were lost or had to be jettisoned. Light cruiser Miami was also damaged. However, it was the destroyers that suffered worst. A number of destroyer commanders had refrained from ballasting partially empty fuel tanks in anticipation of refueling, which reduced their ships' stability, and when the typhoon hit there was not enough time to ballast. Hull, which was at 70% fuel capacity and had not ballasted, was capsized by a 110 knot (126 mph) gust. Monaghan suffered a similar fate. Both were Farragut-class destroyers whose design was notoriously top heavy, but Fletcher-class destroyer Spence also capsized, in spite of its more stable design. Three other destroyers barely escaped the storm. The destroyer escorts, whose design had been criticized by the British for being too stable, fared better than the fleet destroyers. In addition to the three destroyers and nearly 800 sailors lost, seven other ships were seriously damaged. Nimitz described this as the largest uncompensated loss to the Navy since Savo Island.

A Court of Inquiry led by Hoover exonerated the commanders and crews of the lost ships, finding that the preponderance of fault lay with Halsey. Even so, its criticisms were muted. Halsey was responsible for "errors in judgement under stress of war operations and not ... offenses" (Melton 2007). Nimitz and King declined to take any further action against Halsey. However, as a result of the typhoon, Nimitz sent out detailed instructions for dealing with violent weather, the Americans hastened to establish more weather stations throughout the area, and weather reconnaissance flights became more frequent and regular. Three PCEs were converted to weather ships to operate in the breeding ground of the Philippine Sea.

Halsey was unlucky. During the opening moves of the Okinawa campaign, Turner ordered an LST force to continue on to Okinawa in spite of a typhoon forecast. Unlike Halsey, Turner got away with it: The LSTs encountered no storm core and just managed to make their operational schedule.

|

U.S. Navy. Via Morison (1959). |

U.S. Navy. Via Wikimedia

Commons |

Halsey tangled with a second typhoon on 5 June 1945. This storm formed around 1 June north of Palau and was being tracked on 4 June as Halsey refueled. The exact position of the storm remained uncertain until 2200 June 4 when Ancon got a radar bearing on its center. This gave the storm a speed of 26 knots (30 mph or 48 km/h) which Halsey simply refused to believe. As with the earlier storm, Halsey misjudged its course and sailed part of his fleet directly into the path of the storm. Pittsburgh had her bow torn off, but because the crew were at battle stations, there were no men in the forward berths and no loss of life. The bow remained afloat and was eventually towed to Guam. Two other cruisers, a destroyer, and four carriers suffered less serious damage, and six sailors and 76 aircraft were lost,

Halsey's second blunder into the path of a typhoon

nearly ended his career. The Court of Inquiry recommended that

"'serious consideration' be given to assigning Admirals Halsey and

McCain

'to other duty'" (Morison 1959). Secretary of the Navy Forrestal

wanted

Halsey retired but relented after being persuaded that this would

boost

Japanese morale. However,

McCain was transferred to a shore assignment.

References

Typhoons and Hurricanes: The Effects of Cyclonic Winds on Naval Operations (accessed 2008-1-11)

The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia © 2007-2008, 2011, 2015, 2016 by Kent G. Budge. Index