![]() The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia

The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia

|

| Previous: Oil | Table of Contents | Next: Oita |

Mare Island

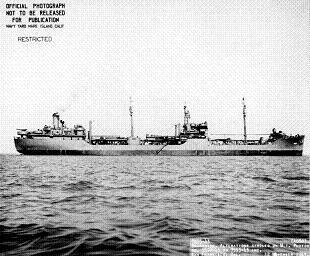

#5595-43. Via Navsource.org

Oilers are ships

designed to supply fuel oil to other

ships

and

forward bases. In the U.S.

Navy classification system, no distinction was made between oilers and

tankers,

except that those oilers that were capable of refueling a ship while

under way

were eventually redesignated as AORs. Informally, the term "oiler" was

used for ships capable of replenishment at sea and "tanker" was used

for ships that merely carried oil from port to port.

The U.S. Navy considered fuel ships the ideal platforms

for testing new machinery,

since they were fairly large ships that were heavily operated, but were

not as essential as warships and would be less of a risk if the

machinery did not work out well. Thus, Maumee

was the first surface ship in the Navy built with diesel engines, while

collier Jupiter was the first

Navy ship with turboelectric drive. Jupiter

would later be converted to the Navy's first aircraft carrier and

renamed Langley.

The officers of Maumee

speculated about the possibility of refueling ships under way, which

had never been attempted before except in the calmest conditions. The

crew obtained schematics for destroyers

and sketched out schemes for refueling at sea, but it was not until the

U.S. Fleet began deploying its destroyers to Europe after the U.S.

intervention in the First World War that Maumee began experimenting with

underway replenishment. The approach used was broadside refueling,

where the ship being refueled came alongside the Maumee.

However, at this early stage in the development of the technique, the

destroyer was towed by the oiler, rather than keeping station under its

own power.

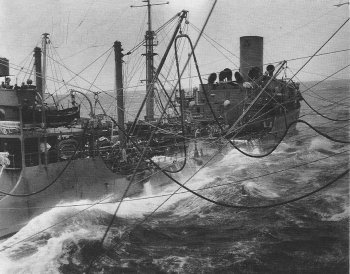

National Archives. Via Wildenberg (1996)

Both the Americans and the Japanese practiced

underway refueling between the wars and had a number of oilers equipped

for this

task. It was found that over-the-stern fueling, where the ship being

refueled was towed by the oiler, was impractical for larger warships.

It was not possible to build a tanker with reasonable characteristics

that could refuel a battleship

in this manner. Enough power was required to run the oil heaters

(required to warm the oil so it would not be too viscous to pump), the

oil pumps, and the tension engine (which kept the oil hose at the

correct tension to avoid either parting or dropping into the cold ocean

water) that the remaining power was sufficient to maintain a speed no

better than six knots, which was unacceptable. Broadside refueling of carriers under way was

first attempted by the U.S. Navy in 1939, was found to be practical in

spite of the seamanship required, and became the standard

practice.

The U.S. Navy' contingency plan for war in the Pacific,

ORANGE,

envisioned an enormous fleet train that included 100 or

more oilers. However, funding for naval construction became very tight

in the late 1920s, and it was not until 1933, when prospects for

funding began to improve, that specifications for new fleet oilers were

developed. The most difficult requirement was high speed, at least 16

knots, to allow oilers to keep up with a general rate of advance of 10

knots while slowing periodically to refuel ships. There were also

requirements to have a range of 6000 nautical miles (11,000 km) on the

ship's own fuel bunkers, a capacity of at least 10,000 tons of fuel oil

plus excess capacity for commensurate lubricating oil, the capability

to ship gasoline in place of fuel oil, a heavy defensive battery, and

deck space for crated aircraft

and landing craft. These

requirements were out of the question for the bulk of civilian tankers,

even with subsidies, so the Navy made a distinction between fleet

auxiliaries capabile of keeping up with the main battle force and

auxiliaries acceptable for naval service. The latter were expected to

be converted merchantmen, while the former would either be built for

fleet service or would be subsidized with the features needed for fleet

service, such as more powerful machinery for higher speed.

During Fleet Problem XVIII in 1937, there was

considerable difficulty maintaining a speed of advance of 14 knots by

Base Force. This led to a recommendation that all fleet auxiliaries have a

minimum sustained speed of 18 knots.

When funding became available for modern Navy auxiliaries in 1937, the Navy argued that it would be far more cost effective to subsidize civilian tankers with appropriate speed and other characteristics than to build its own tankers. This proposal was implemented with the Cimarron and several of its sisters, which were taken over by the Navy after being built for Standard Oil with subsidies for more powerful engines and better hull forms. This became the pattern for virtually all the oilers used by the Navy in the Pacific War.

The Japanese Navy also heavily subsidized civilian

tanker construction, concluding as the Americans had that this would be

more cost effective than continuing the construction of Navy tankers.

Under the stimulus of the subsidies, Japanese tanker tonnage more than

tripled from 1934 to 1940, reaching 364,000 tons. The higher speed of

the new ships mean that carrying capacity more than quadrupled,

reaching 4 million tons per year by 1940. Of the 49 oceangoing tankers

Japan possessed in 1940, 33 were capable of 16 knots or better. A

number of these ships were requisitioned just before war broke out as

the Kyokuto Maru class, and total Navy tanker requisitions by 7 December 1941 amounted to 270,000 tons — a huge fraction of total available tanker tonnage.

When war did break out, neither navy had enough

oilers. However, the

Americans eventually built

large numbers of these ships, while the Japanese lacked the industrial

base to

make good their deficiencies. The U.S. Navy economized its fleet oilers

by employing them close to the combat zone, chartering commercial

tankers to bring oil to forward bases where the fleet oilers refueled.

An important innovation in American oilers was the

retrofitting of spar decks (raised platforms) over the main deck. These

were originally installed to raise the cargo winches and the refueling

crews above the level of turbulent waves in heavy seas, but they

quickly began serving as general cargo decks, allowing the oilers to

carry spare hose and fittings as well as drums of lubricating oil and

other general stores for the ships being refueled. By the autumn of

1944, delivery of oxygen and acetylene tanks, provisions and general

stores, and ammunition had become a regular part of the oilers' role in

the fleet train, and all oilers were instructed to leave port with 150

drums of lubricating oil. At about the same time, oilers began using

the Elwood or wire-span method, which allowed ships to refuel at a

greater distance from each other (60 to 180 feet or 20 to 60 meters).

This allowed refueling at greater speeds and in rougher weather.

British

planning had always assumed that there would be refueling

bases close to any theater of action, and British proficiency at

underway refueling was poor even as late as 1945. While an American carrier could refuel in two

hours, a British carrier took all day.

T2-SE-A1 class

T3-S

class

T3-S2

class

References

Hastings

(2007)

Wildenberg (1996)

The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia © 2007-2009 by Kent G.

Budge. Index