![]() The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia

The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia

|

| Previous: Amoy | Table of Contents | Next: Amphibious Command Ships (AGC) |

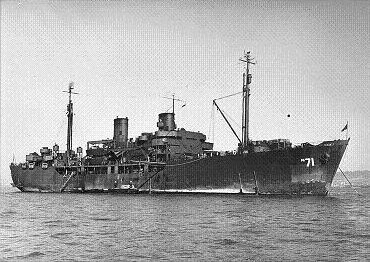

National

Archives

#80-G-415308

Amphibious assault is the military operation of landing troops on

a shore under fire. It is rightly regarded as one of the most

difficult of military operations. Defending positions usually have

good cover and excellent

fields of fire against boats approaching the shore and troops on

the beach. On the other hand, the assaulting troops lack cover and

are unable to move quickly while coming ashore. Logistics is a major

difficulty for the attacker, since the usual port facilities for unloading ships are absent.

Until the beachhead is secured, there is no rear area in which to

deploy artillery and other

supporting arms.

During the First World War, the Allies suffered a costly defeat

in their amphibious assault on Gallipoli, a strategy for which Churchill took much

of the blame. Most military strategists in the interwar years

assumed that a successful amphibious assault against determined

opposition was impossible. A prominent exception was the U.S. Marine Corps, which was

looking for a new mission and found it in the Navy's contingency

plan for war with Japan, Plan Orange. This plan

called for an advance across the central Pacific to the Philippines, which

would require the capture by amphibious assault of defended

islands in the Mandates. As

a result, while Japan, Britain,

and the Unites States all studied amphibious operations between

the wars, only the United States identified a need to the

capability to conduct opposed landings. Murray and Millett (1996)

assess the American understanding of amphibious operations when

war broke out as unequaled by either Britain or Japan, though

actual capability lagged.

The amphibious doctrine of

1919 was primitive. The Navy envisioned loading 50-foot motor

launches with as many Marines as they could carry, then towing

them toward shore while the warships fired a few shells at enemy

positions. The Navy did not consider an effective bombardment to

be a realistic hope because of the belief that "a ship's a fool to

fight a fort", meaning that warships should not operate in range

of fortified coastal artillery, and also because the ships

would have to carry both armor-piercing shells for use against

enemy warships and high explosive

shells for use in the bombardment. There was also the problem of

finding suitable landing sites, since motor launches had a very

wide turning radius.

However, in 1931 three Marine majors, Charles Barrett, Pedro Del Valle, and Lyle Miller, began work on the Tentative Manual for Landing Operations. Their effort was informed by the landing exercises in Hawaii in 1932, the first joint landing exercises since 1927. On 14 November 1933, all classes at Quantico were suspended and all students and instructors were put to work refining the manual. The Marines closely studied the Gallipoli campaign and concluded that it could have succeeded with the right landing doctrine. The Tentative Manual for Landing Operations, which has been characterized as "as much a catalogue of problems that would have to be solved in an amphibious assault as a guide to its execution" (Spector 1985). However, in many respects it proved remarkably prescient in its assessment of the requirements for a successful amphibious assault. Some of the problems it identified were that naval artillery fired on too flat a trajectory for land targets and had only limited reserves of ammunition; the proper use of air support was unknown; and ordinary ship's boats were completely inadequate to transport attacking troops from ship to shore. The last problem was in many respects the key to the situation.

In 1935, the first Fleet Landing Exercise (FLEX-1), involving all

three services (Army, Navy, and Marines) was held off

southern California. Four more joint FLEX were held through

1938, while FLEX-5 (1939) and FLEX-6 (1940) were strictly

Navy-Marine exercises.The lessons learned contributed both to the

1938 Landing Operations Doctrine, USN (FTP-167), the

successor to Tentative Manual for Landing Operations, and

to the the revisions of Plan Orange.

Control of the Sea and Air. Before an amphibious operation could be seriously considered, there had to be a reasonable expectation that the invading force could secure and maintain control of the sea and air in the operational area. Amphibious forces were highly vulnerable, since they were usually loaded in ships build according to civilian designs with limited speed and little capacity for self-defense. Besides providing an adequate escort for the invasion convoy, the invasion commander generally needed to provide a covering force that could strike at any enemy force that materialized to pose a threat to the invasion.

Where the invasion took place out of range of friendly land-based

fighter aircraft, as most of

the Allied invasions in the Central

Pacific did, the invasion force had to bring along its own

air cover in the form of aircraft carriers.

During the Centrifugal

Offensive, the Japanese avoided making landings out of range

of land-based fighter cover, which was aided by the long range of

the Zero fighter. This

proved particularly important in the Philippines, where the

availability of the Zero meant that only the landings at Legaspi and Davao required carrier cover.

This in turn meant that the six first-line carriers of 1 Air

Fleet were available for the strike against Pearl Harbor. The Allied

invasions in the Central Pacific were far outside fighter range,

and air cover was provided primarily by escort carriers, since

the fleet carriers

were allocated to the covering force and did not linger in the

immediate invasion area.

The Allied toehold on Guadalcanal remained precarious for many months precisely because the Americans did not have control of the sea and air around the island. The numerous air and naval engagements in the Solomons after the Guadalcanal campaign followed a similar pattern, but on a lesser scale. Other landings that provoked a major Japanese attempt to wrest control of the sea and air away from the Allies were the Biak invasion (Operation KON), the Marianas invasion (Operation A-Go) and the Leyte invasion (Operation Sho-Go). None of these attempts were successful, though KON came very close.

Only 14% of modern amphibious operations have succeeded where local air superiority was not achieved (Speller and Tuck 2001).

Another vital aspect of sea control, prominent in official

histories of the Pacific War but not often mentioned in popular

works, was sweeping for

enemy mines. An invasion force

must come as close to the beach as possible to land its force,

rendering it vulnerable to mines, which are shallow-water weapons.

However, the Japanese were weak in the area of mine warfare

(consistent with the overall Japanese doctrinal emphasis on

offense and neglect of defense) and they did not accomplish nearly

as much with mines as they might have. Nevertheless, the Iwo Jima invasion (where the

ocean bottom dropped off extremely rapidly away from shore) was

the only Allied invasion of the Central Pacific campaign that was

not preceded by a lengthy mine sweeping operation, and the

invasion of Corregidor was

marred by losses of destroyers

at Mariveles that hit

unswept mines. The latter may be an indication that Japanese mine

warfare did show some improvement over the course of the war.

Landing Craft. Craft for transporting troops to shore must be sufficiently shallow in draft to be able to beach high up on the shore; they must enable the troops to disembark very quickly; and they must be able to easily back off the beach to retrieve subsequent waves. There needed to be enough freeboard to prevent the craft being swamped in heavy seas without making the craft inviting targets for shore guns. Ordinary ship's boats do not meet these requirements. The United States found a solution in the LCVP or Higgins boat, based on marsh boats developed by Andrew Higgins of Louisiana. These boxy, flat-bottomed craft were driven by a recessed drive shaft and propeller that was protected from grounding damage and had a bow ramp that could be dropped in very shallow water to allow troops to disembark rapidly. They thus met all the requirements previously outlined for a landing craft.

Experience in early operations made it clear that larger landing

craft would be required, capable of carrying vehicles, including tanks to support the landing.

This led to the development of the LST,

an oceangoing ship with bow doors that could land surprisingly

high up on a beach and disembark vehicles.

Another development was the LVT or amtrack, an amphibious tracked vehicle that could swim to shore and crawl out of the water and on inland. This was the one purely American innovation in landing craft, other designs having British or Japanese roots. These were lightly armed and armored and proved to be the key to successful amphibious assaults in the central Pacific. At Tarawa, where conventional landing craft were hung up on the reef and their passengers slaughtered, the amtracks were able to crawl across the reef and turn the tide of the battle. It was unfortunate that only a relatively small number of these craft were available. Later assaults were much more lavishly equipped with LVTs, but these relatively expensive craft were never able to completely displace simpler types of landing craft.

U.S. Marine

Corps. Via ibiblio.org

Another important development was the LSD, an oceangoing vessel with a large dock in the stern that could be flooded by ballasting down the vessel. This dock could hold a number of smaller landing craft and launch them much more easily than a conventional transport, which had to lower its landing craft from davits and load the men from cargo nets. By the end of the war, it was becoming clear that the ideal amphibious fleet was spearheaded by LSDs carrying amtracks and supported by LSTs or other ships capable of landing tanks and vehicles.

During the invasion of Guadalcanal,

insufficient manpower was assigned to unloading supplies and

moving them inland, and as many as a hundred boats were beached

for unloading at one point while another fifty waited offshore.

Based on this experience, the Marines added a pioneer battalion to each of their divisions whose job was to

unload the supplies. Unsurprisingly, the pioneer battalion was

often used as replacements for the rifle companies of the division once

the bulk of the supplies were ashore, and since the pioneers were

often black Marines

rejected for service elsewhere, this provided the opening wedge

for introducing black Marines to combat. By the time of the New Georgia campaign, the

Allies reckoned that manpower requirements for unloading supplies

were 150 men for each cargo

ship and transport, 150 men per LST, 50 men per LCT, and 25 men per LCI.

Naval Historical Center #NH 98709

Sea Lift. In late 1943, the sea lift requirements for a reinforced division of about 20,000 men (three regimental combat teams, their ammunition, 1500 vehicles, and supplies) was reckoned at 12 attack transports, three attack cargo ships, and one LSD. Each regimental combat team was carried by a transport division consisting of 4 attack transports and an attack cargo ship. A corps headquarters and supporting units required four attack transports and four attack cargo ships, in addition to those required for its divisions. For the landings on Tarawa, the immediate logistical allotment was 1322 pounds of supply per man, not including fuel and heavy weapons and ordinance. Each attack transport carried about 1100 men into combat.

If the distance was short then some of the sea lift could take the form of short-range beaching vessels such as LSTs and LCIs.

By early 1945 the U.S. Navy had organized transport squadrons

composed of 15 attack transports, six attack cargo ships, 25 LSTs,

10 LSMs and one LSD. Each

could land a fully equipped division on a hostile shore. Eight

such squadrons were organized in time for the Okinawa landings.

The U.S. Army made some important contributions to amphibious doctrine in the area of logistics, at which it excelled. During the invasion of Attu, 7 Division pioneered the use of palletized supplies. The use of pallets caused friction between Holland Smith and Ralph Smith in the rehearsal for Makin, since the Marine commander wanted a full rehearsal and the Army commander feared this would require extensive reloading of the pallets. Eventually a compromise was worked out, but this likely contributed to later tension between the commanders leading to the "War of the Smiths."

Availability of shipping was the chief limiting factor on what

the Allies could undertake throughout the war. The U.S. Navy

had emphasized warships to the almost complete exclusion of

auxiliaries in its prewar expansion plans, and had just 38

transports and 38 cargo ships at the end of 1941. None of these

was a specialized amphibious vessel. The shortage of amphibious

assault shipping was a particularly strong constraint in the

Pacific. By June 1944 the allocation in the Pacific was as

follows:

| Location |

APA |

AKA |

APD |

XAP |

AGC |

LSD |

LSI |

LCI |

LST |

LCT |

LCM |

LCVP |

LCA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. West Coast |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

41 |

0 |

1 |

60 |

181 |

0 |

| Central Pacific |

25 |

8 |

13 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

72 |

72 |

70 |

281 |

1105 |

0 |

| South Pacific |

16 |

5 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

13 |

33 |

60 |

215 |

751 |

0 |

| Southwest Pacific |

4 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

56 |

30 |

70 |

702 |

442 |

0 |

| British Far East |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

2 |

67 |

0 |

46 |

Thus, at the time of the Marianas campaign, there was sufficient

assault shipping in the Central Pacific for about two divisions,

and the combined shipping resources in the South Pacific and

Southwest Pacific were sufficient for less than two divisions. The

invasion of the Marianas required the loan of many of the attack

transports in the South Pacific, plus the use of a significant

number of ordinary (non-APA) transports pressed into the role of

assault shipping.

U.S. Army. Via

ibiblio.org

Fire Support. Until a beachhead could be secured in which artillery could be deployed, the troops ashore had to be supported by naval firepower. This proved problematic. Warships carry a limited number of shells and fire them on much shallower trajectories than is usually the case with land artillery. It was found at Tarawa that naval bombardment was not nearly as effective as had been hoped. Experiments at Kahoolawe in Hawaii showed that naval bombardment had to be highly accurate plunging fire to have much effect on Japanese fortifications. The Navy's older battleships, including survivors of the attack on Pearl Harbor, became the heart of the amphibious bombardment force, freeing the more modern battleships to escort carrier task forces.

Naval fire support was carefully coordinated during the Allied

counteroffensive across the Pacific. Each battalion had a naval

shore fire control party, controlled by the regimental naval

gunfire liaison team. Each Marine division had a naval gunfire

officer (normally a major) and there were special staff at corps level and above.

Another source of fire support was the landing craft themselves, which were fitted with increasingly heavy armament. In addition, a number of amtracks were fitted with tank turrets ("amtanks") to provide direct fire support, while other landing craft were fitted with large batteries of rockets that could deliver a devastating barrage.

Air support was an important component of fire support from the

very start. However, it took some time to learn how to make air

support effective. Fighter-bombers like the Corsair were fitted with

rockets and bombs, including napalm bombs, as the war

progressed. Air support typically was flown from task units of escort carriers,

leaving the fleet carriers

free to provide distant cover or carry out supporting raids deep

into Japanese territory.

Towards the end of the war, fire support become so effective that the Japanese largely abandoned efforts to hold at the water's edge, and turned to defense in depth, out of range of direct naval gunfire. This pattern was first seen at Peleliu. The Japanese plan in the event of an invasion of the Japanese home islands called for the defenders to stay well back from the beaches until the Allies were ashore, then engage them as closely as possible to nullify the Allied long-range firepower.

U.S. Marine Corps. Via ibiblio.org

Intelligence. A successful opposed landing must have adequate intelligence about the target. The attacker must know where his landing craft can cross any reef and successfully beach themselves, and the locations of enemy fortifications must be pinpointed for the preliminary bombardment. Intelligence was obtained by photoreconnaissance aircraft, by submarines taking photographs through their periscopes (though these were of limited value), and by underwater demolition teams scouting the reef and beach while demolishing natural and man-made obstacles with explosives. Photoreconnaissance aircraft took both high-altitude stereoscopic pairs of photographs for mapping purposes and oblique photographs from very low altitude that gave a ship's-eye view of the target.

Nautilus spent

18 days taking 2000 photographs of Tarawa

prior to the invasion. However, she could not obtain information

on the reef inside the atoll, nor could she identify many of the

gun positions for destruction by the preliminary bombardment.

The presence of submarines, reconnaissance aircraft, and

frogmen was an obvious sign that a coast was about to be invaded,

so intelligence gathering was a trade off for security. Krueger has been

criticized by historians such as Taaffe (1998) for his reluctance

to risk giving away surprise by more fully employing his Alamo Scouts, particularly

at Biak, where lack of reliable

intelligence seriously handicapped the Allied invasion. Security

could be enhanced by sending reconnaissance missions against

several plausible targets, so that the enemy was left guessing

which was the actual target. Where the strategic situation was

such that the next target was obvious, there was little to lose by

mounting a thorough reconnaissance, as was done at Okinawa and Iwo Jima.

U.S. Navy. Via

ibiblio.org

Command and Control. An amphibious assault was an

exceedingly complicated operation, requiring that large numbers of

small craft arrive at the right points at the right time and in

coordination with their fire support. This required superb command

and control. The solution, as with so many other problems in

amphibious operations, was specialized ships and small craft.

At the top was an amphibious

command ship, usually a specially modified transport, that

carried the assault force commander and his staff and was equipped

with extensive communications facilities. These replaced the battleship or other large

warship favored as flagships by some early assault force

commanders, which proved unsuitable because their firepower could

not be spared from the preliminary bombardment. The blast of their

guns often knocked out their own communications.

In addition to the amphibious command ship, an LCC was eventually assigned to each transport division to control the landing craft. These were supplemented by submarine chasers and surplus LCVPs acting as wave guides (typically four to eight for each wave). Most of the landings were made in broad daylight, and the control craft typically employed brightly colored flags to identify themselves and the landing beach to which they were assigned.

The Marines themselves carried the TBX, a portable radio designed

by General Electric. This was fully waterproof and sturdy enough

to take considerable abuse.

It is perhaps unsurprising that there was considerable contention

early in the war over who should command the amphibious command

force. The sensible compromise that was eventually reached by the

Americans was that the senior Navy officer commanded the force so

long as it was at sea and during the initial assault, while the

senior Army or Marine commander took command once he was able to

establish his headquarters ashore.

The British prepared a manual on amphibious operations (which they usually referred to as combined operations) in 1922, with revisions in 1925, 1934, 1936, and 1938. There were also small-scale exercises (involving single battalions) in 1924 and 1928, taken on the initiative of local commanders, and a brigade-sized exercise 1934 that involved 41 warships. However, these efforts presupposed an unopposed landing, and there was a serious lack of organizational commitment or institutional memory. The Royal Marines shrank to just 9000 men, and their leaders never seized upon amphibious assault as a distinctive mission, emphasizing base defense (in the form of the Mobile Naval Base Defense Organization) instead.

The 1936 revision to The Manual of Combined Operations

finally sparked serious interest in amphibious assault, and the

Inter-Services Training and Development Centre opened in July

1938. Its director, Captain L.E.H. Maund , who had observed the

Japanese operations in 1937, won the support of Majkor General

Hastings Ismay, who noted that (as quoted in Murray and Millett

1996):

... as our strong suit was command of the sea, we should be making poor use of our hand if we relegated combined operations to the background of our war plans. Indeed it seemed that we should be laying ourselves open to justifiable criticism if we made no effort in time of peace to train on modern lines for a possible combined operation in time of war.

However, the British had completed just eight experimental Motor

Landing Craft (MLC) by 1939, when it was estimated that several

hundred were required to land a division, and the prototypes were

too heavy to be handled by ordinary passenger liner davits. After

war broke out, work accelerated on the LCA and LCM, while Churchill, as First

Lord of the Admiralty, inaugurated a crash program to develop the

LST.

U.S. Marine Corps. Via ibiblio.org

The Japanese began World War II with near parity in

amphibious capability and doctrine with the United States. The

Japanese Navy and Army were unusually cooperative in the

development of amphibious doctrine, in spite of maintaining

separate amphibious forces (of which the Army's was the larger),

holding joint exercises in 1922, 1925, 1926, and 1929. These were

large exercises, with three divisions involved in the 1922

exercise. The lessons learned from these exercises were distilled

into the "Outline of Amphibious Operations" (Joriku sakusen

kōyō) of 1932, which predated the Tentative Manual for Landing Operations and

became the Japanese bible of amphibious warfare. The Army

Transportation Service organized shipping engineer regiments of 1200

officers and men to operate landing craft, debarkation units to to

load or unload transports either through ports or over a landing

beach, and managed its own port facilities and Army shipping

through shipping transport commands.

Following the Shanghai

Incident of February 1932, in which the Japanese rikusentai

at Shanghai clashed with Kuomintang

troops and took heavy casualties,

the Navy organized the Special Naval

Landing Forces. These were activated at the four major naval

bases (Sasebo, Kure, Yokosuka, and Maizuru) and numbered in order

of activation. By 1941, they closely resembled Army battalions in

organization,

equipment, and tactics.

The Japanese avoided opposed landings whenever possible. During

the Centrifugal

Offensive this was almost always possible, because the

Japanese had command of the sea and Allied forces were stretched

very thin. Japanese amphibious forces tended to land in columns

rather than waves, in order to concentrate at the point of attack.

The only two attempts by the Japanese to land under heavy fire

both took place at Wake; the

first attempt failed before the assault troops had even gotten

into their boats, and the second succeeded only with heavy casualties in spite of

overwhelming numbers and massive air and naval support.

In spite of a doctrine of avoiding opposed landings, the Japanese made some important innovations in amphibious craft that often closely paralleled those of the Allies. Indeed, many respects, the Japanese were well ahead of the Allies when war broke out. For example, the Japanese had already developed landing craft, such as the Daihatsu, that strongly resembled the LCVP in form and function. The Japanese Army experimented with amphibious tanks as early as the 1926 exercises. The Japanese Army and Navy also cooperated in the construction of Shinshu Maru, the first ship laid down specifically for landing operations. Japanese innovation reached its peak with the Akitsu Maru, which could carry and launch both landing craft and aircraft. This prefigured some of the features of postwar amphibious assault ships.

U.S. Army. Via ibiblio.org

The Japanese Army remained preoccupied with the Soviet threat until September 1943, when the Army schools finally switched their emphasis to countering American tactics. Prior to that time it was assumed that the Navy would take responsibility for fighting the Americans. Emphasis was originally put on counterattacks against the beachhead, but when this doctrine proved unsuccessful (particularly at Peleliu, where a Japanese tank-infantry counterattack was cut to ribbons while a defense in depth in the high terrain held up the Americans for a month) the Army was force to change tactics. The Army issued its Essentials of Island Defenses in August 1944, which called for a mobile defense anchored to strong points from which local counterattacks could be launched. Fortifications, dispersal, concealment, and fighting spirit were emphasized. In October a new draft was released that abandoned defense at the water's edge and called for defense in depth. However, it proved difficult to overcome a generation of training that emphasized cold steel and offensive spirit, and the Emperor himself questioned why the commander at Okinawa abandoned the airfields to the Americans rather than defend the beaches.

References

The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia © 2006-2011, 2013, 2016 by Kent G. Budge. Index