![]() The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia

The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia

|

| Previous: Dolphin, U.S. Submarine | Table of Contents | Next: Doolittle, James Harold |

U.S. Navy

James Doolittle was a former Army aviator who became the country’s leading civilian test pilot between the wars. He was recalled to active duty well before the attack on Pearl Harbor and helped organize the expansion of the Air Corps. In April 1942, Doolittle was ordered to plan a carrier raid on Tokyo. Because of the weakness of the U.S. Navy at this point in the war, and the anticipated strong defenses of the Japanese homeland, the raid was conducted by medium land-based bombers whose crews were specially trained at carrier takeoffs. Because landing back at the carrier was out of the question, the bombers were to proceed to China and reinforce the Nationalist air forces.

The directive to launch a raid on Japan originated with Roosevelt, but the unlikely source for the idea of having land-based aircraft attack from a carrier was a submarine officer on King's staff. King passed the suggestion on to Arnold, who had Doolittle perform a feasibility study that identified the B-25 as the only bomber in the American inventory capable of taking off from a carrier, attacking Tokyo, and flying on to friendly bases in China.

Doolittle selected and trained a

group of 24 volunteer crews from 17

Bombardment Group, which had been flying B-24s longer than

any other formation in the Army Air Forces. The crews were trained

in

great secrecy at Eglin Field, Florida, where a naval aviator,

Lieutenant Henry F. Miller, provided instruction in very short

takeoffs. The crews were also trained in low-level flying and

night navigation. They were to approach their targets at low

altitude, then climb to 1500' (460m) for their bomb runs. Their

aircraft were specially modified for increased range, including

the installation of additional fuel

tanks in place of the ventral gun turret, and their Norden

bombsights were removed. The crews were trained to use a simple

"Mark Twain" bombsight in place of the Norden, which was

considered too sensitive to use on a raid where there was a high

probability of the Japanese recovering a crashed American

aircraft.

The crews and sixteen of the aircraft embarked on the Hornet

at Alameda

and sortied for Japan on 2 April 1942. The Hornet task

force was joined en route by Halsey’s

task force built around the Enterprise,

which would provide fighter

cover.

U.S. Navy. Via ibiblio.org

The original plan called for a

takeoff from 450 miles out

timed so that the bombers would arrive over the target after

dark. However, as early as 10 April, the Japanese had hints

from traffic analysis

that an American carrier force might be headed for Japan. The task

force was spotted by Japanese picket boat Nitto

Maru #23 at 0738 on 18

April 1942, while

still 800

miles from Japan. The picket

boat was promptly sunk by gunfire, but not

before it was able to transmit a warning to Tokyo. Halsey ordered

Doolittle to launch at once rather

than further risk

half the Navy’s carrier strength, and Doolittle's aircraft took to

the air at 0818. As a result of the early launch, the

raiders arrived in

daylight, but the Japanese defenses were taken by surprise and Doolittle's

fliers made

their bombing runs unscathed.

The Japanese had received the picket boat warning, but assumed

that the Americans planned a raid with conventional carrier

aircraft, and calculated that the raid could not be launched until

the next day. The main Japanese carrier strike force had just

completed a raid into the Indian

Ocean, far to the west, and was unable to intercept the Hornet

task force, which made a clean escape.

The material damage done by the

raid was

relatively minor. The raiders each carried three 500 lb (227 kg)

demolition bombs and an

incendiary cluster, and these were targeted on oil stores, factories, and military

establishments. One bomb hit the carrier Ryuho, which was

undergoing reconstruction at Yokosuka

Navy Yard, delaying its

completion by some months. The other damage was quickly repaired.

Some of the bombs went wide of their targets and hit heavily

populated neighborhoods, which provided a pretext for the later

mistreatment of captured raiders.

U.S. Army. Via ibiblio.org

Because of the early takeoff, none of

the raiders made it to

friendly Chinese airfields.

One

plane, which suffered a

carburetor

malfunction, landed at Vladivostok

where the crew were interned

by the Russians.

Although a favorable tail wind allowed the other fifteen aircraft

to reach the China coast, miserable weather and night conditions

prevented any of them from landing at the Chinese airfields. The

aircraft crash-landed or their crews bailed out after their

aircraft

ran out of fuel. Three raiders were killed bailing out or in crash

landings. Another eight raiders fell into Japanese

hands. The

remainder were spirited out to Chungking

and, eventually,

back to the United States.

The Japanese were outraged by the attack, which caused the military great loss of face. Sugiyama Gen felt particularly humiliated, and persuaded Tojo to pass retroactive regulations subjecting captured bomber crews to the death penalty. The eight raiders captured by the Japanese were accused of strafing civilians and were treated as war criminals, three being executed by firing squad and another dying in captivity. The raid also muted most of the opposition to Yamamoto’s Midway operation, though the decision to proceed with the operation had already been made and the plan presented to the Emperor two days earlier. This ill-conceived operation would prove disastrous for the Japanese. The Doolittle raid was a tremendous morale booster for the Allied public at a time when good news was very scarce. If the measure of success of a military action is its political results, then the Doolittle raid must be regarded as a resounding military success, notwithstanding its negligible material impact.

The most concrete military effect of the raid was that the

Japanese retained four fighter

groups in Japan in 1942-1943 that were badly needed elsewhere.

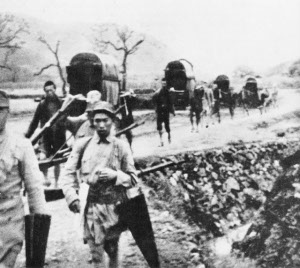

The East China Campaign. Chiang Kai-shek had

only reluctantly agreed to the raid, fearing the likely Japanese

reaction. He was also told few details of the plan, since the

Americans did not trust Chinese operational security (for example,

the Americans knew from ULTRA

that the Japanese were reading Chinese codes.) Chiang did not give

his consent for the raiders to land on Chinese airfields until 28

March, and it was not until 2 April that he was told the

approximate number of aircraft involved and the airfields they

would be landing at.

Chiang's fears were well-founded. In

retaliation for Chinese involvement in the Doolittle Raid, and

possibly because they mistakenly believed that the raid had been

launched from China (Peattie et al. 20111), the Japanese

Army went on a rampage in China,

killing an

estimated quarter of a million Chinese civilians. Some 140,000

Japanese troops from five divisions

and three independent mixed brigades

of 13 Army participated

in

a sweep of airfields in Chekiang

and

Kiangsi provinces in mid-May

1942 and also stripped the

Chekiang-Kiangsi

rail line of

rolling stock. After linking up with two divisions from 11 Army at Nanchang, the Japanese pulled

out of

the area. Chinese

military casualties were

estimated at 40,000, while the Japanese suffered 1600 dead and

28,000

wounded.

References

Craven and Cate (1952; accessed 2012-8-12)

The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia © 2007-2010, 2015, 2016 by Kent G. Budge. Index