![]() The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia

The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia

|

| Previous: Prinz Van Oranje Class, Dutch Minelayers | Table of Contents | Next: Pro Patria, Dutch Minelayer |

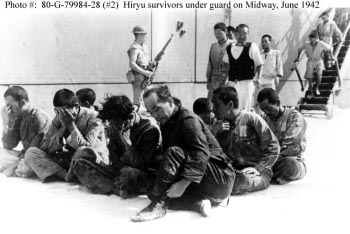

National

Archives

#80-G-79984-28-2

Prisoners of war, or POWs, were military personnel who had surrendered and were entitled

to

certain protections under the Geneva and

Hague

Conventions. Only lawful combatants were entitled to these

protections. Persons who engaged in combat while not wearing

distinctive insignia visible from a distance; who were not

part of a chain of command

back

to a legal sovereign; or who did not bear arms openly or abide by

the laws and customs of war, were unlawful

combatants and had no protection under international law. They

were

generally executed as bandits by both Axis

and Allies if taken

prisoner.

POWs were theoretically entitled to the same rations, medical

care,

and pay as their captors. Enlisted men could be required to

perform

nonmilitary work for pay, but officers

could not be required to work.

Punishment for attempted escape was limited to 30 days solitary

confinement. POWs charged with more serious offenses were entitled

to

trial by military tribunal in the presence of a neutral observer. This

was usually a representative of a protecting power acting as an

intermediary between the belligerent powers. On

conclusion of hostilities, POWs were required to be repatriated

within

a reasonable time frame. In practice, these protections were

mostly

observed between the

western Allies and the European Axis.

These rules regarding prisoners of war were adopted for both idealistic and realistic reasons. Properly guarding, transporting, and caring for prisoners of war consumed significant resources that might otherwise have been available for military use. Nations that accepted this obligation made a powerful statement that upholding certain basic rules of humanity was important enough even to risk defeat in time of war. However, there were also pragmatic reasons for proper treatment of prisoners, not least of which was the likelihood that mistreatment of prisoners would become known and would deter enemy troops from surrendering. There was also the likelihood that mistreatment of prisoners would provoke retaliation in kind. Prisoners were also potential sources of intelligence, and, to some extent, prisoner labor could replace drafted civilian labor.

It may seem strange that men engaged in the business of killing

other men and destroying their works should be expected to behave

in a

humane manner towards enemy captives. However, the right to

quarter

(the opportunity to surrender) established by the Conventions was

an important check on wartime violence. An army is not just a

murderous

mob; it is an instrument of state policy that must remain under

firm

control to prevent it becoming no more than a murderous

mob.

Rules regarding wartime conduct generally, and rules regarding

prisoners of war in particular, were an important aspect of

maintaining

that control.

| Nation |

Prisoners of war |

Number of deaths |

Death percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia |

21,726 | 7,412 |

34.1 |

| India |

68,890 | ||

| Japan |

41,440 |

||

| Netherlands

East Indies |

37,000 |

8500 |

22.9 |

| United

Kingdom |

50,016 | 12,433 |

24.8 |

| United States |

21,580 |

7107 |

32.9 |

Japan signed both the Geneva

and

Hague Conventions but ratified only the Hague Conventions, which

had less to say about prisoners of war. The failure to ratify the

1929

Geneva Convention was due to pressure from the Japanese Army,

which was

undergoing a profound shift in its attitude towards conduct on the

battlefield. In previous conflicts, such as the Boxer Rebellion,

the

Russo-Japanese War, and the

First World War, the Japanese Army had been

notably correct in its treatment of prisoners of war. Of the 4,592

German

prisoners taken by the Japanese during the First World War, only

82

died in captivity, primarily from the 1918 influenza pandemic.

This

reflected

the desire to establish Japan as a respectable member of the

international community in equal standing with the Western powers.

However, by 1929, Japanese Army leaders had become convinced that

Japan's national aspirations would never be satisfied within the

existing international order. This eroded support for compliance

with

international standards of military conduct, as did the growing

emphasis on absolute obedience to the Emperor. Japanese Army

officers at distant posts on the Asian mainland, particularly with

Kwantung Army,

were influenced by their proximity to the brutal warlord struggles

in China, and their attitudes

propagated throughout the Army.

The Japanese had insisted on unconditional

surrender of Allied forces in the Philippines and

southeast

Asia in the first months of the war, and they took the position

that

unconditional surrender meant that even the Conventions did not

apply.

Navy Minister Shimada

Shigetaro told the Cabinet on 20 March 1942 that Japan would

not

respect the Second Hague Convention with regard to prisoners of

war, on

the grounds that Britain had waged "extreme warfare based on

retaliation and hatred" (Browne 1967).

Under bushido,

as characterized by samurai professor Inazo Nitobe in

1907, captives were to be treated with mercy, but this injunction

failed to

make

it into the code of the modern Japanese Army. During the Pacific

War, Allied

prisoners of war were

regarded by the Japanese as completely dishonorable and were

subject to

appalling treatment. It did

not

help that discipline within the

Japanese Army itself was brutal, and many of the prison camp

guards

were Korean conscripts

who were at

the bottom

of the military pecking order. Lieutenant Geoffrey Adams, a

British prisoner on the infamous Burma-Siam Railroad,

became acquainted a Korean guard, nicknamed "Kaneshiro" ("The

Undertaker") because he was the camp coffin maker. "Kaneshiro"

engaged in petty fraternization with the prisoners, and, possibly

in retaliation, he was confronted by a Japanese non-commissioned

officer for a trivial violation of regulations and beaten

unconscious. Mistreated by

their Japanese NCOs, the Korean guards mistreated Allied prisoners

in turn, a pattern

that one Japanese critic has described as "transfer of oppression"

(quoted in Hicks 1994). An anecdote from Hastings (2007)

illustrates

the concept:

Ito had been constantly brutal. The POWs had no inkling that he spoke English until suddenly he addressed a terse question to Abbott: "Homesick?" ... He asked curiously what Abbott thought of the Japanese, and received a cautious reply: "I don't know them very well, so I cannot answer your question." The guard persisted: "How do you think of what you know? How do you think of me?" Abbott said: "In our army, we do not strike and beat people as punishment. Ito is always doing so, and this blackens my thoughts about him." The eyes of the little Japanese widened in amazement. He asked how the British Army punished wrongdoers. Abbott explained that physical chastisement was unknown. Ito never hit a prisoner again.

Tojo set the tone for much of the treatment of prisoners of war on 25 May 1942, declaring that (Hoyt 1993):

The present situation of affairs in this country does not permit anyone to lie idle, doing nothing but eating freely. With that in view, in dealing with prisoners of war, I hope you will see that they are usefully employed.

He elaborated shortly afterwards to prospective POW camp commanders:

In Japan we have our own ideology concerning prisoners of war which should naturally make their treatment more or less different from that in Europe and America. In dealing with them you should, of course, observe the various regulations concerned and aim at an adequate application of them. At the same time you must not allow them to lie idle doing noting but enjoy free meals, for even a single day. Their labor and technical skill should be fully utilized for the replenishment of production, and a contribution thereby made towards the prosecution of the Greater East Asia War for which no effort might be spared.

Tojo's statements were superficially innocuous. Under the

international conventions, it was permissible to require enlisted

POWs

(but not officers) to work. They could not be required to perform

work

of immediate military value, such as arms production, but they

could be

put to work on food production, railway construction, or other

activities of indirect military value. However, Tojo's statement

became

license for local commanders to make slaves of POWs, who were

neither

paid nor given sufficient food to remain physically fit. Tojo's

admonishment not to allow POWs to rest for even a single day meant

that

POWs worked seven days a week, and working hours were brutal,

sometimes

exceeding 18 hours a day. Worse still, Tojo's instructions led to

a

practice of refusing food to POWs who were too sick or injured to

work.

Assignment to prison camps was considered demeaning, so it is

likely

that camp commanders represented the worst of the Japanese officer

corps. Many stole the Red Cross food parcels that were sent in

large

numbers for the prisoners, while others withheld hundreds more

tons of

Red Cross parcels until after the final Japanese surrender.

Parcels

from family members were also withheld. One camp commander on the

Burma-Siam Rairoad ordered the

prisoners' band to play the dwarves'

work tune from the animated film, Snow

White ("Hi, ho, hi, ho, it's off to work we go") as the

starving

inmates were mustered into work details each morning. The

commander at Camp O'Donnell on Luzon,

Tsuneyoshi Yoshio (known as "Baggy Pants" to the prisoners),

received survivors of the Bataan

Death March with an angry tirade that included the declaration

that Roosevelt

and MacArthur

would be hanged once Japan had occupied Washington, D.C. At age

51,

Tsuneyoshi, a graduate of the Japanese military academy, had not

yet

advanced beyond the rank of captain. Tsuneyoshi's

incompetence was too much even for the Japanese, and after a few

months

he was sacked and the prisoners sent to other camps. Postwar he

was

sentenced to 6 years' imprisonment, but was released in a general

amnesty.

The Japanese almost invariably executed prisoners of war who

attempted to escape. In some camps, the prisoners were coerced

into

signing agreements that they would not attempt escape, allowing

the

Japanese to apply the legal fiction that prisoners who attempted

escape

were being executed for mutiny or desertion.

Military discipline tended to disintegrate among Allied prisoners of war, though some captive commanders, such as Maltby, were able to restore a measure of discipline. Maltby forbade individual escapes on the grounds that the Japanese would retaliate by withholding food, endangering the lives of the remaining prisoners. On the other hand, Maltby seriously considered organizing a mass escape in spite of predictions that a third of those escaping would perish. These plans never came to fruition. The Japanese eventually separated senior commanders from their officers and officers from men, which aggravated discipline problems.

The International Red Cross proved ineffective at applying pressure on the Japanese to improve camp conditions. Red Cross officials who visited the Hong Kong POW camps cabled back reassuring reports that gave no hint of how terrible conditions were. One of the officials later claimed that the Japanese were censoring his reports, and anything close to a candid evaluation of conditions would never have passed scrutiny. This official also claimed that the Kempeitai were searching his office and residence weekly for anything incriminating.

Incredibly, some POWs held in countries with a sympathetic local population were able to establish contact with Allied authorities. A group of escaped prisoners from Hong Kong organized the British Army Aid Group, which passed messages to the prisoners via Chinese truck drivers bringing supplies to the camps. In one camp, an electronics technician was able to construct a radio transmitter. The prisoners sent back reports on conditions in the camps and on Japanese activities in Hong Kong harbor. The Kempeitai were able to uncover some of these operations and executed three British officers for espionage.

Allied prisoners at Cabanatuan

were able to construct clandestine radio receivers using

extra parts obtained on the pretense that they were being used to

repair their captors' radios. These receivers were able to pick up

the

powerful broadcasts from San

Francisco

and kept the prisoners informed on the progress of the war as seen

from

the Allied side. The prisoners were also able to establish ties

with

the underground network

outside the camp, which was able to smuggle in

vitally needed food to keep the prisoners from starving.

Allied authorities were reluctant to believe that the Japanese

treated their prisoners as badly as they did. Japanese POWs

claimed

under interrogation that

Allied POWs were well treated, perhaps out of fear of retaliation,

or

perhaps because they believed their own propaganda. As

late as January 1945, the British

Political Warfare Committee suggested that mistreatment of Allied

POWs

was the exception rather than the rule, taking place mainly in

isolated

areas far from Japan where local military authorities were less

well

controlled. Such illusions were shattered within months as large

number

of POWs were released in the Philippines and Burma. Their stories

were

so shocking

that the Allied governments sometimes censored them for fear of

their

own citizens' reactions. In particular, American authorities

feared

that stories about Japanese atrocities would undermine the "Germany First" policy.

Hell Ships. The Japanese attempted to move large numbers

of POWs from southeast

Asia to Japan. The prisoners were packed into the holds of

merchant ships under appalling conditions, and the ships were not

marked in any way to indicate that POWs were aboard. As a result,

many

of these "hell ships" were sunk by Allied submarines and aircraft. The

Japanese made little effort to rescue the survivors, although a

number

were picked up by American submarines.

In one notorious incident, Lisbon

Maru was sunk by U.S. submarine Grouper

on 1 October 1942 off the China

coast. The ship was abandoned by the Japanese, who left 1,816

British

POWs locked below decks with inadequate ventilation. When the

prisoners

broke out of the hold, five Japanese guards who had been left

behind

fired on them. At about this time the ship finally foundered in

shallow

water, and the prisoners found themselves in the water with four

Japanese gunboats shooting

at

them. Some 843 were shot or drowned

before the survivors were finally rescued. The captain of Lisbon Maru, Kyoda Shigeru,

was

later sentenced to seven years' imprisonment by a British military

tribunal.

Mortality rates tell the story as well as anything. Whereas 4% of

western POWs held by the Germans

died in captivity, 27% of western POWs held by the Japanese

perished in the prison camps. The contrast is particularly great

for

the Americans: Of 24,992 American soldiers captured by the

Japanese,

8,634 or 35 percent died in captivity, whereas just 833 or 0.9

percent

of the 93,653 American soldiers captured by the Germans died in

captivity (Frank 1999).

The Japanese evidently considered killing all their prisoners of

war

rather than let them be repatriated by the Allies in the event of

an invasion of Japan. On 16

August 1945, the Japanese Navy Ministry sent out an order that

included the following:

All papers relating to prisoners and interrogation (particularly those such as the ones published in December 1944 which refer to interrogation of American pilot prisoners), and confiscated ——, together with this dispatch are to be immediately and positively disposed of in a manner that will offer the enemy no pretext.

This order strongly hints that the Navy Ministry had previously issued orders to execute prisoners of war, which orders were subsequently destroyed. A Marine sergeant in a prisoner of war camp outside Himeji testified (Frank and Shaw 1968):

In 1944. . . Tahara came to me and advised "I am very sorry — we must all die." Tahara told me that orders had been issued by Tokyo which would require, the moment the first American set foot on Japanese soil, that all POWs be killed and that the camp authorities then commit suicide.

Shortly afterwards, the Japs began daily drills. A platoon of Japs would arrive at our camp from Himeji barracks (they were required to move on the double for the 11 kilometers), hastily set up their machine guns to completely encircle the camp and execute other maneuvers clearly indicating a plan they wished to execute without mistake. Their arrival, their maneuver, their critique, and their departure took place two or three times each week. The . . . authorities made mention that the soldiers were being trained to protect us from irate civilians who might wish to harm us if U.S. troops started to invade. On one occasion, I made a point blank statement to the [Japanese second in command], Sgt. Fukada, that it was regrettable that we should have to die after so long a term in prison camp — he agreed and stated he would have liked to have lived after the war was over, perhaps the country would some day be a good country again.

I believed that orders directing massacre of the prisoners had been issued and am still of that opinion.

A number of captured airmen in Japan were in fact murdered after the Emperor broadcast the surrender. On the other hand, Major General Matsui Hideji released his prisoners of war before retreating from Rangoon; those in hospital were found by the DRACULA invasion force. Regrettably, those released prisoners who attempted to walk to the British lines were wearing old-style khaki uniforms resembling those of the Japanese, rather than the newer British jungle green uniforms, and were attacked by Allied aircraft that mistook them for a Japanese column.

China. The war in China produced few prisoners of war on

either side until

the mass surrender of Japanese troops at the end of the war. The

Japanese released only 56 Chinese prisoners of war at the end of

hostilities, after eight years of fighting a Chinese army whose

strength peaked at around 6 million men. This was in spite of

Japanese records showing the capture of thousands of prisoners,

including 9,581 in the Wuhan campaign alone (Peattie et al.

2011). It is faintly possible that some Chinese prisoners of war

were given their paroles or were impressed into puppet forces, but

it is much more likely that captured Chinese troops were generally

shot or beheaded out of hand.

The Japanese military ethos regarded surrender as completely

dishonorable. The 159 Japanese soldiers captured at Nomonhan in 1939 and

repatriated by

the Soviets were severely

punished

by their own army. Enlisted men were assigned to penal units and

officers were ordered to commit suicide.

The message was clear, and prisoners of war constituted not more

than

3% of Japanese casualties

even

in the final campaign at Okinawa.

Those who did offer surrender sometimes engaged in perfidy,

turning on

their would-be captors with a grenade

or knife.

Some Allied units became reluctant to offer quarter, with the

result

that many

Japanese

did not survive their attempt to surrender. Captain John Burden, a

former physician working with Japanese immigrants in Hawaii who

was the

first Japanese language officer on Guadalcanal, reported that on

"several occasions word was telephoned in from the front line that

a

prisoner had been taken, only to find after hours of waiting that

the

prisoner had 'died' en route to the rear. In more than one

instance

there was strong evidence that the prisoner had been shot and

buried

because it was too much bother to take him in" (quoted in Straus

2003).

However, those Japanese POWs who made it to the rear were usually treated humanely, in part because Allied intelligence officers considered prisoners to be valuable intelligence assets. The Japanese did nothing to prepare their men for the possibility of capture, since that possibility was unthinkable, and Japanese prisoners tended to talk freely with their captors if treated well. Many Japanese prisoners begged their captors to allow them to remain in Allied countries and to not inform their government of their capture rather than face the dishonor of returning alive to their families. These requests were refused, since such notification was required under the Conventions, although fully half the prisoners gave false names to interrogators to avoid shaming their families. Many of the prisoners felt that by being taken captive they had ceased to be Japanese, and some prisoners even helped the Americans draft propaganda leaflets.

The Americans interned captured Japanese at Camp Paita in New

Caledonia, though most were eventually transferred to seven

camps on

the U.S. mainland. Spain acted as the protecting power for

Japanese

prisoners of war in the United States until April 1945, when the

massacre of the Spanish consulate at Manila caused Spain to break

relations with Japan. Japanese captured by

Commonwealth forces were interned at Camp Bikaner in present-day

Pakistan; Camp Cowra, Camp Hay, and Camp Murchison in southeast Australia; and Camp

Featherston near Wellington,

New Zealand.

Prisoners thought to have particularly valuable information were

sent

to either Fort Hunt or Camp Tracy, where they were kept in

wiretapped

rooms and subject to thorough interrogation. Even here, however,

there

was little or no use of duress to extract information.

Sometimes Japanese prisoners of war did not remain

psychologically

broken. There were two instances of riots at Allied prisoner of

war

camps,

where the actions of the Japanese prisoners suggest that they had

decided it was better to regain their honor by being shot while

attempting escape than to continue to endure the shame of

captivity.

The riot at Camp Featherston on 25 February 1943 took place when

250

prisoners refused to

report for work, the situation escalated, and 48 prisoners and one

guard wound up dead. The mass breakout at Cowra on 4 August 1944

resulted in the escape of 359 prisoners, all of whom were

subsequently

either recaptured, killed while resisting recapture, or committed

suicide. The Cowra breakout ultimately cost the lives of 231

prisoners

and four guards. A third planned riot at Camp Piata was exposed by

an

informer, and the ringleaders promptly hanged themselves in their

barracks.

Both riots were led by a hard core of "true believers", prisoners

who maintained a deep faith in the ultimate victory of Japan. At

Featherston the ringleaders were petty officers from cruiser Furutaka,

while those at Cowra were noncommissioned officers upset that they

were

going to be separated from their men. The ringleader at Piata was

Senior Petty Officer Sato Mitsue, who was "a dyed-in-the-wool

Imperial

Japanese Navy warrior type — 'self-confident, dignified, exuding

authority'" (Straus 2003).

However, while many POWs professed to interrogators that they

wished

to be killed, relatively few seemed to really mean it.

Interrogators

sometimes became so annoyed with requests from POWs to be killed

that

they invited the prisoner to make a run for it so that he would be

shot

by the military police

while attempting escape. None took the interrogators up on the

offer.

Japanese prisoners of war feared the worst when they returned to

Japan after the war. For the most part, their fears went

unrealized,

and they were able to reintegrate into Japanese society relatively

smoothly. One ex-POW even rose to flag rank in the postwar

Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force.

Few Japanese were taken prisoner by the Chinese prior to August

1945. One recent estimate is that about 8300 Japanese had been

taken

prisoner by Chinese forces by 15 August 1945. Both the Japanese

and the Chinese generally executed captured enemy soldiers out of

hand. However, the Japanese

capitulation led to the mass surrender of some 1.2 million

Japanese

troops in China. Expecting vicious retribution from the Chinese,

the

Japanese instead found their treatment by the Chinese to be

"magnanimous" (Straus 2003). The Kuomintang were primarily

concerned with ensuring that the Communists did not

gain any advantage from captured Japanese weapons, from the power

vacuum in formerly Japanese-controlled areas, or by directly

employing

surrendered Japanese troops against the Kuomintang.

Russia had not signed the Conventions, and both Russian prisoners and prisoners of the Russians were treated with great brutality in the European war. The brief Russian campaign in Manchuria in August 1945 resulted in the capture of numerous Japanese prisoners, who were generally also treated quite poorly. Some were not repatriated until 1956. American researchers estimate that the Soviets captured 2,726,000 Japanese nationals during the campaign, of which only a third were military. Of these, 2,379,000 eventually returned to Japan. Some 254,000 were confirmed dead, and the remaining 93,000 were presumed dead. However, this 13% death rate, while appalling, was far less than that of either German prisoners in Russia or Western prisoners of the Japanese.

References

Frank and Shaw (1968; accessed 2012-6-15)

Harmsen

(2013)

Hastings

(2007)

Hickman (2009; accessed 2012-4-14)

Lindsay

(2005)

Newman (1995)

Russell

(1958)

The Pacific War Online

Encyclopedia © 2007-2013, 2015 by Kent G. Budge. Index